Is downside risk the critical driver of investor asset valuation? In the January 2013 version of their paper entitled “Conditional Risk Premia in Currency Markets and Other Asset Classes”, Martin Lettau, Matteo Maggiori and Michael Weber explore the ability of a simple downside risk capital asset pricing model (DR-CAPM) to explain and predict asset returns. Their approach captures the idea that downside risk aversion makes investors view assets with high beta during bad market conditions as particularly risky. For all asset classes (but focusing on currencies), they define bad market conditions as months when the excess return on the broad value-weighted U.S. stock market is less than 1.0 standard deviation below its sample period average. To test DR-CAPM on currencies, they rank a sample of 53 currencies by interest rates into six portfolios, excluding for some analyses those currencies in highest interest rate portfolio with annual inflation at least 10% higher than contemporaneous U.S. inflation. They calculate the monthly return for each currency as the sum of its excess interest rate relative to the dollar and its change in value relative to the dollar. They then calculate overall and downside betas relative to the U.S. stock market based on the full sample. They extend tests of DR-CAPM to six portfolios of U.S. stocks sorted by size and book-to-market ratio, five portfolios of commodities sorted by futures premium and six portfolios of government bonds sorted by probability of default, and to multi-asset class combinations. They also compare DR-CAPM to optimal models based on principal component analysis within and across asset classes. Using monthly prices and characteristics for currencies and U.S. stocks during January 1974 through March 2010, for commodities during January 1974 through December 2008 and for government bonds during January 1995 through March 2010, they find that:

- The specified threshold (average return minus 1.0 standard deviation) for bad U.S. stock market conditions generates 55 bad months out of 435 during the currencies sample period. An alternative threshold of 0.5 (1.5) standard deviation below the average generates 118 (27) months.

- Regarding the interaction of currency returns and U.S. stock market conditions (see the chart below):

- Returns increase monotonically from low-interest rate to high-interest rate currencies, with the volatility of high-inflation currencies pronounced. High-interest rate currencies have market betas that are higher during bad market conditions than good market conditions.

- Consequently, carry trade (long high-interest rate and short low-interest rate currencies) returns relate more positively to U.S. stock market returns during bad months (correlation 0.33) than during good months (correlation 0.03).

- Results are robust for a subsample restricted to developed country currencies.

- DR-CAPM explains the cross-section of returns within each of equities, commodities and government bonds. For all three asset classes, portfolios that have higher market betas during bad market conditions than good market conditions earn higher average returns. DR-CAPM also explains the joint cross-section of returns for combinations of the four asset classes.

- Within each asset class, DR-CAPM captures the cross-sectional dispersion in returns related to the most important principal components. Across asset classes, the single DR-CAPM factor captures the expected returns derived from as many as eight principal components.

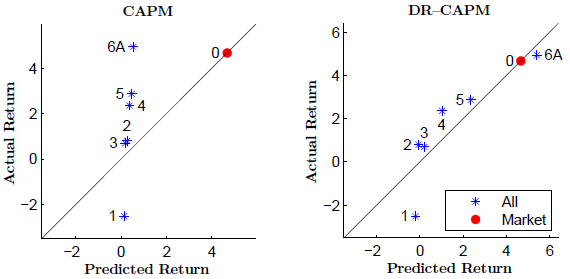

The following charts, taken from the paper, relate actual gross annualized average returns for six currency portfolios ranked each lagged month by interest rate to gross annualized predicted returns based on overall beta (CAPM) and on downside beta (DR-CAPM). All returns are in excess of the risk-free rate. The portfolio with the highest interest rates excludes currencies with extremely high inflation rates. The red circle (0) indicates the average annual excess return of the U.S. stock market. The sample period is January 1974 to March 2010 (435 months). Calculations for beta, downside beta and the threshold that defines downside are all in-sample, using the entire sample period.

Results indicate that overall beta is not useful in predicting currency portfolio returns, while downside beta works well.

In summary, evidence indicates that, while overall beta is not useful, beta relative to U.S. stock market returns during bad times relates positively to expected returns within and across a broad set of asset classes.

Cautions regarding findings include:

- Portfolio returns reported in the study are gross, not net. Including the trading frictions associated with monthly portfolio turnovers would reduce these returns. Turnovers may vary across ranked portfolios in ways that diminish the downside beta effect.

- Elevated volatilities for portfolios with high downside betas may work against cumulative returns.

- As noted, the study employs in-sample relationships to estimate portfolio betas and the threshold for bad market conditions. This approach is not suitable for evaluating trading strategies. In other words, an investor operating in real time would calculate different values for betas and the bad market threshold as data accumulates. Moreover, during extended bull markets for U.S. stocks (no recent bad market conditions), calculation of current downside betas would be problematic.

- While mitigated by robustness tests, the selection of one standard deviation below average as the definition of bad market returns may incorporate data snooping bias.